Folk and fairy tales are omnipresent in the world today. Cultures developed these stories from their oral traditions and specific histories in an attempt to explain the world around them while being entertaining at the same time. As a result, these tales, however fantastic, either refer to or are based in the real world in some fashion. Therefore, when J.R.R. Tolkien created his world of Middle-earth, with the idea that it stand as the long-lost ancient history and mythology of this world, he understood that what he was writing would necessarily need to remind readers of their own world. To this effect, the geography is similar, the customs and lives of the Hobbits are familiar, and Tolkien even made sure to include origins of common sayings in the English vernacular (Hobbit 98). Even the long-ago stories of the history of Middle-earth, resonate with readers. This is because Tolkien had such a firm grasp on the concept of “fairy-stories,” as he referred to them, and how they were adapted in this world over the years (“Fairy” 35). Specifically, he understood how history itself can be adapted in this way to become folk or fairy tales (“Fairy” 35). Looking carefully at some of the key tales in the pseudo-history of The Silmarillion, readers can see Tolkien’s take on the genesis for several Folk and Fairy Tales popular today. In the chapter titled “Of Beren and Lúthien,” Tolkien gives readers his idea of the historical basis for the common folk tale, “Rapunzel” (189-221).

To compare these two tales, a short summary of “Rapunzel” is needed. The tale begins with a married couple soon to have their first child. During her pregnancy, Rapunzel’s mother gets a craving for Rampion, a herb also known as Rapunzel. There is some growing in the garden behind the couple’s house, but it belongs to an enchantress. The wife convinces her husband that she will die without any of the herb, so he goes into the garden and steals some. This only makes her hungry for more, but the second time her husband tries to steal some he is caught by the enchantress. This results in a deal that the couple must give the enchantress their child when it is born. After the child is born, the enchantress names her Rapunzel and, when she is around twelve, locks Rapunzel in a tower located in the center of a forest, and which has no entrances or exits. The only way in or out for the enchantress is by climbing Rapunzel’s long, golden hair. Being very lonely, Rapunzel takes to singing in her tower in a most beautiful voice. After two years of this imprisonment, the King’s son[1] hears her singing in her tower and, after spying how the enchantress enters, meets Rapunzel and convinces her to escape with and marry him. They plan for her to weave a ladder out of silk he will bring her every time he visits. Unfortunately, Rapunzel unwittingly betrays their plan to the enchantress who then cuts off Rapunzel’s hair and sends her to live in the desert. When the King’s son comes the next night, he climbs up the hair that the enchantress has cut from Rapunzel. After discovering what has happened, he casts himself out of the window and falls into a thorn bush whose barbs blind the King’s son. Disfigured and blind he roams the forest eating nothing but “roots and berries,” until he comes upon Rapunzel in the desert. When she recognises him, she cries over his face healing his eyes. They return to the kingdom and have a wonderful life together (Grimm 73-76).

A close inspection of Tolkien’s tale in The Silmarillion, “Of Beren and Lúthien,” illuminates some undeniable plot similarities to the Grimm’s recording of “Rapunzel.” The forest of Doriath, surrounded by the protective, magical Girdle of Melian is analogous to the walled garden owned by the Enchantress in “Rapunzel” as well as the forest that Rapunzel’s tower is located in. Like the King’s son, Beren spends time wandering in the forest eating “no flesh” (191). When Lúthien and Beren finally meet, it is as a result of her singing and his calling of her (new) name (193). After this meeting, when Lúthien leaves Beren, he is struck with a type of blindness that only her presence can cure (194). These comparisons are fairly basic and stay fairly true to the Grimm’s version of the tale.

There are two instances when Tolkien’s tale becomes not only more complex in its comparison, but also seems to portray themes that are not congruous with the Grimm’s version. Given Tolkien’s understanding of the evolutionary aspects of folk tales discussed above and his wish to have his writing stand as a history of this world, these variations are not surprising and even add credibility to his creation. The first of these instances is when Beren meets with Lúthien’s father, King Thingol. In this scene, Thingol takes on the role of the Enchantress in “Rapunzel.” When Beren declares his desire to marry Lúthien, Thingol demands a most unreasonable price that Beren readily accepts, “Bring to me in your hand a Silmaril from Morgoth’s crown; and then . . . Lúthien may set her hand in yours” (196). This reflects the enchantress demanding Rapunzel as the price for herbs from her garden and Rapunzel’s father’s quick acceptance of this high price. However, Tolkien has some fun with the idea here. Rapunzel’s father makes his decision while under the terror of the Enchantress and it is implied that he may not have fully understood what he was doing (Grimm 74). However, in Tolkien’s version, Beren is fully aware of the implications of Thingol’s demand and regards the demand a small one indeed: “For little price, do Elven-kings sell their daughters. . . . (196). Indeed, the bravado of Beren, combined with the nature of his relationship with Lúthien, reveals him as a combination of the characters of Rapunzel’s father and the King’s son.

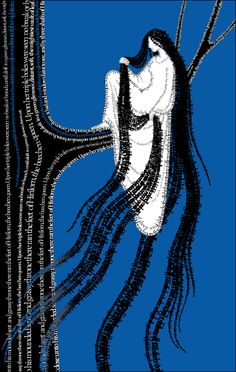

The second instance, although the most obvious connection between Tolkien’s tale and the tale of “Rapunzel,” still manages to skew the theme presented in the Grimm’s version. It occurs when Lúthien is imprisoned by her father (already identified as the equivalent of the Enchantress) in a house with no available access points, high in a tree in the forest of Doriath. In Tolkien’s tale she escapes this prison by causing her hair to magically grow long, weaving it into a cloak of shadow and sleep, and a rope, also endowed with the power of magical sleep. Lúthien uses the rope to cause the guards below to fall asleep and then to climb out of her prison. Then, using her shadowy cloak as protection, she goes off in search of her wandering love, Beren (202). What is significantly different in this telling as opposed to the Grimm’s version is that Lúthien is in control of her own destiny. Where Rapunzel seems to be alternately at the mercy of her parents, the enchantress, or the King’s son, Lúthien takes charge of her situation.

Folk and fairy tales are a natural part of this world’s history. Tolkien, knowing this when he created his version of the ancient, lost history of this planet, made sure to include the possible origins of many myths as well as folk and fairy tales in his writing. However, he was a clever enough writer not to state them more or less verbatim with only cosmetic alterations made. He knew that over the course of history as long as he was creating, tales of this sort have a natural tendency to evolve. Comparing his chapter “Of Beren and Lúthien,” found in The Silmarillion, to the Grimm’s version of the folk tale “Rapunzel,” illustrates exactly how well he understood this evolution. The significant differences between the characters of Lúthien and Rapunzel, as well as the amalgamation of Rapunzel’s father and the King’s son into the character of Beren, attest to this understanding. Undeniably, Tolkien’s tale can be considered the genesis of the story of Rapunzel in a reality where his history of Middle-earth is fact, once again demonstrating his literary genius.

Works Cited

“Rapunzel.” The Complete Illustrated Fairy Tales of The Brothers Grimm. Hertfordshire: Wordsworth, 1997. Print.

Tolkien, J.R.R. “On Fairy-Stories.” The Tolkien Reader: Tree and Leaf. New York: Ballantine, 1966. 3-84. Print.

—. The Hobbit. Revised ed. New York: Ballantine Books, 1988. Print.

—. The Lord of the Rings. 50th Anniversary ed. London: HarperCollins Publishers, 2007. Print.

[1] Interestingly, the son of the King is never referred to as a prince in this tale.

©Ben Melnyk 2011